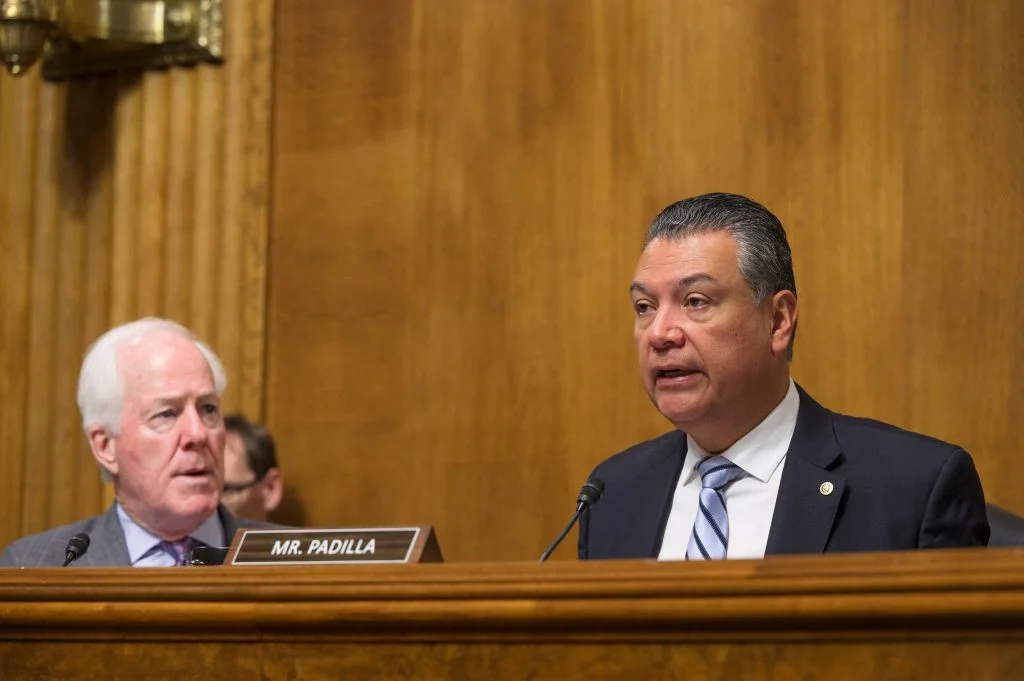

Padilla Leads Hearing to Examine U.S. Immigration Court System and Due Process Challenges

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Today, U.S. Senator Alex Padilla (D-Calif.), Chair of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and Border Safety, convened a hearing titled “Preserving Due Process and the Rule of Law: Examining the Status of Our Nation’s Immigration Courts.” The hearing examined the current structure and function of our immigration courts, including court backlogs, due process issues, and the importance of legal representation.

During the hearing, Padilla heard testimony from The Hon. Mimi Tsankov, President of the National Association of Immigration Judges (NAIJ); Mr. Jeremy McKinney, immediate past President of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) and Founder of McKinney Law; Ms. Rebecca Gambler, Director, Homeland Security and Justice Team, U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO); and Mr. Charles “Cully” Stimson, Deputy Director, Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies, Manager, National Security Law Program, The Heritage Foundation.

Padilla began his remarks by underscoring the U.S. immigration court system’s ongoing struggle to deliver timely and fair adjudications due to a substantial backlog of cases. He also detailed that unlike in criminal proceedings, noncitizens in removal proceedings have no right to counsel at the government’s expense, and representation rates are low, restricting a critical due process safeguard and undermining efficiency and fairness. Currently, less than half of all people with cases before the immigration courts have attorneys — including children as young as one or two years old — and an estimated 80 percent of detained respondents lack representation.

Padilla emphasized that the best approach Congress can take to address the critical issues facing our immigration courts is to establish independent Article I immigration courts. Creating independent immigration courts would be a critical step toward restoring judicial independence, due process, and the rule of law in our immigration courts. He pushed for smart investments in the immigration courts — including funding for support staff for immigration judges, for legal counsel to boost representation, and to support much-needed process and technological improvements within the courts.

During his first round of questioning, Padilla heard from Mr. McKinney on the importance of legal representation for ensuring due process and increasing case efficiency. Mr. McKinney stressed that immigrants who have representation are significantly more likely to gain relief. Judge Tsankov and Mr. McKinney further emphasized the severe challenges unrepresented immigrants have in obtaining relief for which they are eligible, including navigating a dizzying labyrinth of procedural and legal hurdles in the immigration court system.

In his second round of questioning, Padilla heard from Ms. Gambler about the long-standing need for the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) to develop a Strategic Workforce Plan to improve efficiency, better plan for and manage the agency’s staffing needs, and help the agency communicate those resource needs with Congress.

Padilla concluded his questioning by asking Judge Tsankov about the importance of support staff and concerns with political interference in immigration courts. Judge Tsankov detailed the numerous vital roles legal assistants and law clerks play in her court. She also elaborated on the threats to immigration courts’ independence because of their placement within the Department of Justice, which has historically led to political interference in the form of frequent docket shuffling and changes to case law through Attorney General self-certification.

Key Excerpts

PADILLA: Since 2001, EOIR data shows that only 6 percent of immigrants who were unrepresented were successful in winning their cases, whereas having representation makes detained individuals more than 10 times more likely to prevail. Question is for Mr. McKinney. Can you just elaborate further on why having an attorney makes such a difference in outcomes for individuals? And how having representation impacts court efficiencies generally?

McKINNEY: Thank you for the question, Chairman Padilla. As our written testimony indicates, there’s a 2016 study from the American Immigration Council that indicates that represented respondents and immigration courts are five times more likely to gain relief. TRAC, a nonpartisan organization whose numbers we all rely on, points out that those that applied for asylum affirmatively, and then had to defend that asylum application in immigration court, they saw their approval rates go to almost 76 percent because they were nearly all represented. Now, I do want to point out that that still, that 76 percent only still represents a very small number of total grants in our system. But the point is, is that representation ensures due process, but it also makes the system more efficient. When all the parties know the rules and know how to present a case, cases move faster.

PADILLA: Thank you. I also want to bring in Ms. Gambler here for a minute on issues of management and the backlog. Now, thanks in large part to persistent under-resourcing as compared to other immigration enforcement agencies, the courts have long struggled to keep up with the number of cases referred to them by DHS. The court backlog has grown consistently since 2007. As you’ve laid out, it doubled under the previous administration and further increased during the COVID-19 pandemic while many courts were physically closed. Despite a record couple of years of case completions under the current administration, the court backlog is now well over 2 million cases and growing. I want to afford you an opportunity to show what steps could EOIR take to help address the backlog?

GAMBLER: Thank you, Chair. We think it’s critically important for EOIR to address the recommendations that GAO has made to it over the years. Those recommendations are really designed to help improve the management and thus help EOIR improve the efficiency of court operations. And there’s a particular recommendation that I would like to highlight that that is long-standing. And that is the need for EOIR to develop a Strategic Workforce Plan. That is important because that type of workforce planning efforts helps an agency identify what gaps and skills they need to have in their workforce, how they’re going to fill any skill and competency gaps they have, and then monitor progress in doing that. A Strategic Workforce Plan also helps an agency be positioned then to speak with Congress about what the resource needs are and how the agency will go about meeting those resource needs. So this is a long-standing recommendation that GAO has made to EOIR. We made it back in 2017; it’s actually a priority recommendation. And we think it’s critically important that EOIR take action to address that and work on getting a Strategic Workforce Plan in place.

PADILLA: I just want to remind us that from Fiscal Year 2014 to Fiscal 2023, we actually more than doubled the number of judges from 249 to more than 650 thanks in large part to EOIR’s repeated asks to Congress for additional judges. But at the same time, EOIR has been criticized for failing to hire sufficient numbers of support staff for those judges. And from today’s testimony, we hear that that support staff is also desperately needed. Judge Tsankov, just briefly, I’ve asked a lot of very long questions, but just briefly, why are support staff so critical to you, your role and your job and the efficiency of the courts.

TSANKOV: I could not do my job without the few support staff that I do have. They’re phenomenal, working so hard, I sometimes get messages from them at eight o’clock at night. We need our legal staff, legal assistants to notify the parties when hearings are scheduled, to make sure that the hearing notices gets sent out to Mr. McKinney so he comes to court on that day, at the right time. We need them to, when Mr. McKinney files documents before the court, to make sure that those documents get put in the right file so I see them when I hold my hearing a few months down the road. We need them to send out their judicial orders. You know, we have a lot of paper files, so that means that those orders have to be sent out by mail. They take care of all of that. We also need them to be there to answer the phone when unrepresented litigants call with questions. How do I file this document? We also need our judicial law clerks to assist us with legal research on the very difficult questions, not the maybe the cases that are just that take 90 minutes, but the ones that are highly complex with novel questions of law. So we need them.

PADILLA: These are great examples and descriptive of what true courts should be. We’ve talked earlier in the hearing about the independence or the need to strengthen the independence of immigration courts. We referenced how both Democratic and Republican administrations have used immigration courts to influence immigration law and implement change or implement immigration policy and priorities. You know, we’ve heard over the years, the creation of accelerated or dedicated or rocket dockets to prioritize certain types of cases, the imposition of case quotas. We’ve talked already about self-certification. Judge, back to you, why are immigration courts so vulnerable to political interference? And how would truly independent immigration courts address some of these concerns?

TSANKOV: I think that the source of the challenge that we have in terms of this vulnerability regarding independence is the fact that we’re housed within the U.S. Department of Justice. Successive attorney generals have the authority to recertify cases to themselves, it changed the law. All of that results in expanded case dockets. But in addition, when the Attorney General has that power to essentially implement the law enforcement agenda of the executive branch, that impacts our dockets, and creates concerns in terms of lengthy delays for hearings that need to be handled in an expeditious manner and due process provided to them. But also, it causes real challenges for perceptions about fairness in our system. And so, the other thing that we see quite often is that each new administration has different docketing priorities, and that shuffling of the docket results in judges being in one administration sent to the border and their home court dockets languish for extended periods of time. So it’s the docket shuffling, and the issue with the changing case law that I think is the most problematic for our court.

More information on the hearing is available here.

###